Additional Reading / Chapter Two

An artist’s thoughts on limiting color theory

A LITTLE COLOR GOES A LONG WAY

An artist pictures places in his mind. Places he’s been, but also, places only his imagination could go.

In his sketchbook he imagines the entrance to a dark cavern. Somewhere to hide? Or somewhere to find what is hidden? The artist leaves the possibilities unexplored, moving onward to a different tomorrow. A future world where technology moves by undefined means, flowing towards a yet to be decided destination.

On the facing page his mind wanders to somewhere darker. He recalls a long dead tree with limbs outstretched in silent appeal. Fear saturates the place with unease. In the final panel the artist is reminded of everyday places. A pathway through a sunlit meadow, surrounded by tall trees casting a comforting shadow. It is the sort of place he should stay – kept safe and sound with what is familiar. Unfortunately, his thoughts cannot be kept in one place.

The artist struggles to bring these visions to life, he is not quick enough to fully capture the memory before it fades. Or extreme enough to force his visions into reality. This is a lesson the artist has learned many times. And it has taught him to simplify the journey, to ease the passage from mind to matter.

It’s surprising how much storytelling can come from a few tubes of paint. Each of these studies are made using a combination of only three colors. Every shade, tint, and color has its purpose; they hold meaning, elicit an emotional response, and contribute to the storytelling of a picture. Combined they say even more.

three’s company

In the first picture, the foreground is painted using a generous mixture of Burnt Umber and Mars Black. Infusing the tower with an imposing sensation of scale. Ascending stairs are rendered using Titanium White, mixed with just a touch of Burnt Umber. The contrasting values provide a focus, and narrative destination for the image.

In the second image, tints and shades of Burnt Umber yield a wide range of local colors and temperatures. Establishing an atmospheric perspective and depth of field for the narrative setting.

the color makes the space

In the third image, a light foreground to a dark background presents the illusion of entering a foreboding interior space.

The color in image four suggests the reverse. Of leaving a darkened interior and entering a brighter outdoor environment.

The sepia paintings are made using Titanium White, Mars Black, and Burnt Umber. The range of local colors, shades, highlights, color temperatures, and values are infinitely surprising.

feeling blue

The next paintings demonstrate how any limited color palette can build a convincing and emotive narrative. Image five uses Ultramarine Blue, Mars Black, and Titanium White to achieve a dark interior environment and moody atmosphere. In contrast, the blue of image six establishes an industrial and technological cityscape vibe.

Monochrome color plans are the foundation of the artist’s creative process. Painting directly out of the tube can feel artificial, and hard to model convincingly. Using neutral colors to naturalize raw pigments can result in richer, and more subtle color application.

red hot

In image seven, the generous use of Cadmium Red and Mars Black creates an unsettling atmospheric tension. In image eight, the generous use of Titanium White to tint the reds and darks results in a calmer and more meditative scene.

Often the artist uses a monochrome underpainting to form the base structure of an image. Painted over with transparent glazing to establish different local colors, while retaining as much of the underpainting as possible.

EVERYTHING OLD IS NEW

Color Separations

Before computers (the artist was a teenager at the time) coloring a line drawing was done during the printing process. Artists would ink or cut out stenciled overlays designating where the colors should appear. These were called color separations. As an example, a black and white line drawing of Superman would be drawn on a piece of Bristol paper. Then, the red of his trunks, cape, and boots would be inked or blocked in on a transparent overlay using a solid black. Same with the blues of his tights, and so on. This method of color separation is still done in older printing methods such as screen printing and Risographs.

In the images shown, the artist used the fundamentals of color separations to organize his workflow. The first image (top layer) is the line drawing layer. If this was a hand drawn or scanned image, he would use multiply in the layers menu to make the white of the page transparent. The next image is a separation layer for the tree trunk, which is a layer just below the line drawing. As described earlier, the artist blocked in the shape to designate the area he wanted to color. He will also add a clip mask layer above the separation layer, so he can paint expressively inside the separated shape without worrying about coloring outside of the lines. The third image shows the foreground and background layers that further define the scene. The artist organizes his layers in folders called foreground, middle ground, and background. Arranging art layers to reflect spacial depth is intuitive and can organize the atmospheric perspective of the image.

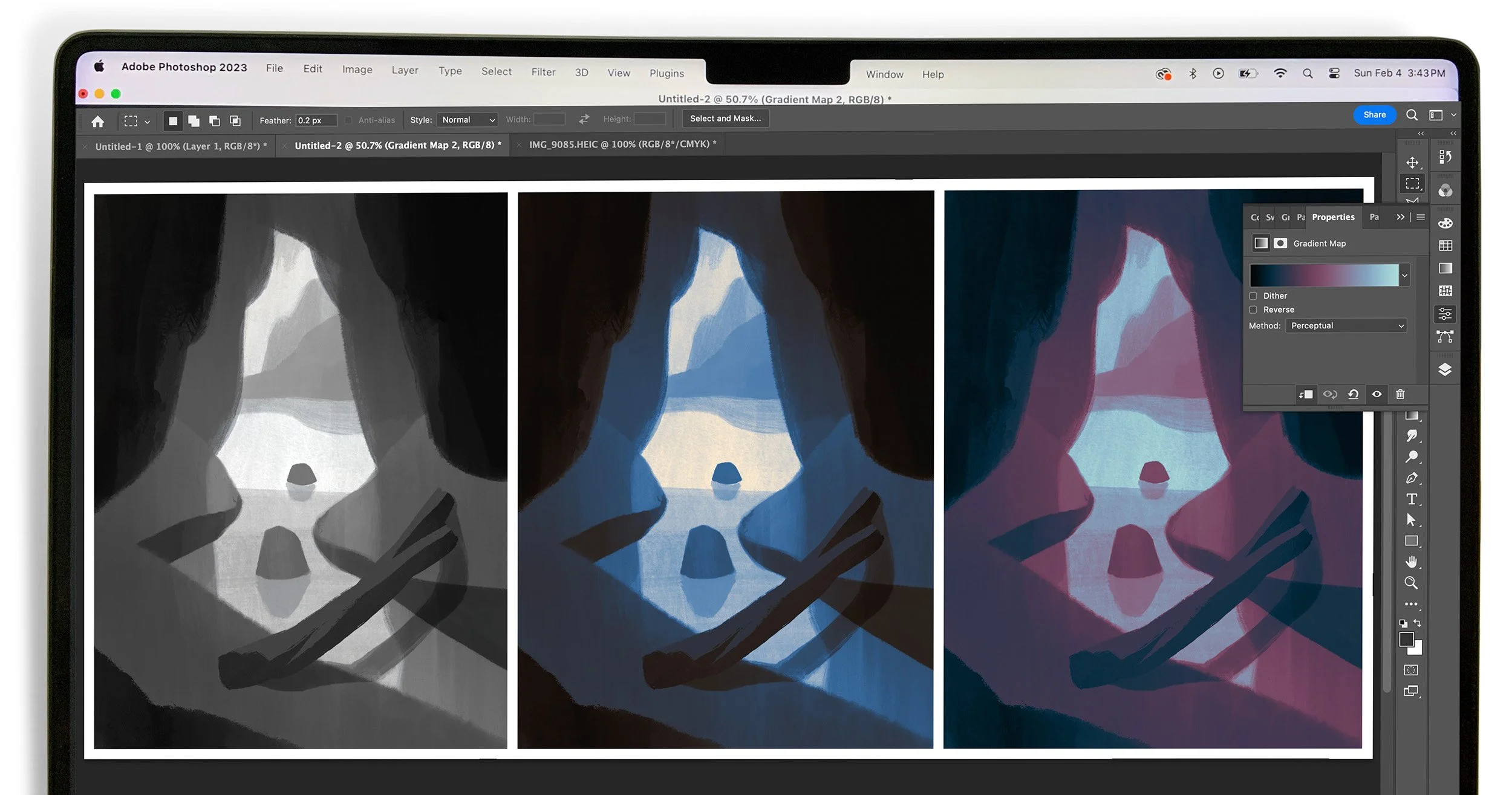

MAPPING COLOR

Changing Color with a Press of a Button

A method to further expand on color separation is using gradient maps. Gradient maps are available in many programs including Procreate and Photoshop. With gradient maps you can assign specific colors to the different values of a grayscale drawing. In the second image the artist designated the lightest values as a light tan color. For mid values he set them as blue, and the darkest values were made to be a warmer temperature black. This is a very quick method to iterate with. For example, in the third image it took only a few mouse click to reassign the lightest values to blue, the mid values to a burgundy red, and the darks to a cooler blue/black. Gradient maps can also create infinitely complex color plans. The artist can add as many color stops as he want, and as many gradient maps as he has layers to effect. He can choose individual gradient maps for specific layers, or even mask out single elements on a layer.